|

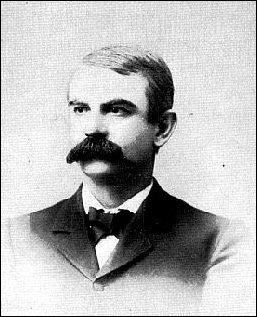

THE WASHERWOMAN'S SONG  Fort Scott author, lawyer, and legislator, about 1881 ON Sunday morning, January 9, 1876, the Fort Scott Daily Monitor printed, without any explanation, Eugene F. Ware's poem, "The Washerwoman's Song," in the form given above. [2] The printing of poetry in the Monitor was not unusual, some being reprints of well known and obscure poets identified by name, some unidentified and on occasion unquestionably local, and some signed pieces by local aspirants to literary recognition identified by name, by initials, or by a pen name. Ware's poem was designated as written for the Monitor and was signed by his pen name "Ironquill," which was already known in a modest way in Kansas. If the editors were impressed by this poem as being any different from their customary poetic contributions, no hint was given, not even a distinctive position or typographical display. The reading public, both local and state, allowed no room for doubt, however, registering immediately and with enthusiasm a hearty approval, even when disagreeing in part with some of the ideas expressed. At Leavenworth, the Times and the Commercial, January 12, the Anthony morning and evening papers at the moment, commented in identical editorials: "The Fort Scott Monitor has an original poem by 'Ironquill,' entitled 'The Washerwoman's Song,' which possesses much more than ordinary merit, and deserves to take rank with Hood's 'Song of the Shirt.'" [3] The poem was printed in both papers a few days later, with the comment that it was "a beautiful little poem by Eugene Ware." [4] The Topeka Daily Commonwealth, January 16, 1876, the Sunday issue, admonished its readers: "Don't fail to read the poetry on the third page, written by Eugene Ware of Fort Scott. It is worth any sermon you will hear today." Two days later, in calling attention to the approval given the poem by the Leavenworth Times, the Commonwealth added its bit of praise: "Eugene never wrote anything better." Whatever the Monitor's private views may have been on Sunday morning, January 9, when "The Washerwoman's Song" was first printed, the editors purred in the reflected sunlight of such praise like kittens who had just licked up a saucer of cream. On January 14 they acknowledged Anthony's approval and added their own first recorded verdict: "It is one of the best poems Mr. Ware has ever written." To be sure, that was a guarded commitment -- "one of the best." Four days later, the Monitor reported the printing of the poem in the Times and the Commonwealth on Sunday, January 16, and the comments. But, in the locals column appeared the following wry verdict -- bluntly practical and materialistic -- "The Washerwoman's Friend -- The person who pays his wash-bill promptly." In another two days, the exchanges received led the Monitor to another self-satisfied acknowledgment: "Eugene Ware's last poem, 'The Washerwoman's Friend,' is going the rounds of the press. Most of our exchanges have published it, and many of them highly complimented it." [5] Again, February 2, the Monitor noticed that it was "going the rounds" having been reprinted in the Leavenworth Times, the Topeka Commonwealth, the Sedalia Bazoo, the Girard Press, and the Columbus Courier, the Humboldt Union, and the Manhattan Industrialist -- "It is one of the most popular of Mr. Ware's productions." "The Washerwoman's Song" was indeed printed widely in Kansas by the weekly press, and the news service that printed "Patent Outsides" and "Insides" thought well enough of it to print it and promptly. [6] The Paola Spirit was among those that commented, not only on the poem, but upon Ironquill's stature as a literary man: Mr. Ware makes no pretension to poetical genius, yet he has already achieved an enviable reputation in the literary circles of the West as a writer of brilliance, not only on the poetical line, but in prose, and the field of wit. The Spirit is only too glad to be able to "pick up" anything written by the gifted and talented gentleman, Eugene Ware -- "Ironquill." He will make his mark. This was reprinted by the Parsons Sun, February 19, 1876, along with the news that Ware had accepted an invitation to read a poem at the Parsons pioneer celebration, March 8. [7]

On home ground the reception of Ware's poem was remarkable and significant. Among the items recorded, the first in the sequence was the publication, in the Daily Monitor, January 18, or nine days after the historic Sunday of January 9, of a "poem" signed "Leon Love" (Thomas M. Nichol): THE WASHERWOMAN'S FRIEND

Nichol had been on the Monitor staff for a time, having resigned in December, [9] and was devoting himself to the promotion of the Kansas Clipper sulky and gang plows which he had invented. These plows had been awarded the first premium at the Kansas State Fair at Leavenworth, which opened September 7, 1874. The Kansas State Grange had been contracted with the Fort Scott Foundry to manufacture them, and this arrangement had brought Nichol from Humboldt to Fort Scott. He was born in Ohio, came to Kansas from Illinois, and in 1876 was 29 years of age. [10] Anthony's papers, the Leavenworth Times and the Commercial, for January 20, ridiculed Nichol's effort at versification. "The fledglings are already attempting to ape Ware's song of the washerwoman. Leon Love's [Nichol's] doggerel in Tuesday's Monitor is the first. You will have to make stronger 'suds' than that, Love, if you expect your clothes to be 'fit to be seen'" In printing this blunt verdict by Anthony, the Monitor attempted, the next day, to draw somewhat the sting with the comment: "Rather rough on 'Leon Love.'" Then, on January 23 (Sunday), by request, the Monitor reprinted both poems, along with the admonition: "They are good Sunday reading." The Fort Scott Pioneer, January 27, the Democratic weekly rival of the Monitor, edited by U. F. Sargent, could not pass up such an opportunity to deride the opposition. His barbed jibe, inspired by Anthony's ridicule, was: "Poor Nichol! His wishy-washy parody on Ware's 'Washerwoman's Song' finds but little favor." And in the same issue Sargent wrote a two-paragraph introduction to an anonymous "poem." Of course, it might have been his own brainchild, whose paternity he did not have the courage to acknowledge. THE WASHERWOMAN'S SONG

This had been preceded in the Pioneer, January 20, by an article in which Sargent had noticed unfavorably the structure of Nichol's versification. Nichol defended himself at length. Though the Pioneer article is missing from the files, he quoted much of it. [11] In printing it the Monitor editor warned his readers in a local: " 'Leon Love' criticizes a critic this morning at great length. In a contest between giants the fur must fly." Also, at the top of the reply, the Monitor accommodated with the headline: "What a Critic! A Few Words About Poetry, Criticism, Ignorance, Stupidity and Meanness" [12] Nichol began by quoting from the Pioneer editorial of January 20 entitled "What a Poet," which had ridiculed his rhyme and had characterized his effort as a "wishy-washy parody on Ware's Washerwoman's Song. . . " In defense Nichol showed a familiarity with a wide range of literature, but he took the ground that principle, not his own verses, was his concern. He condemned the tendency to greet new writers "with words not of welcome and encouragement, but of derision and ridicule." The partisan verdict of the Monitor editor was that: "The worst used-up critic we ever saw, is the universal expression in regard to 'Leon Love' vs. Sargent." [13] Immediately, the Monitor printed another of Nichol's "poems," "The Sentry Boy" which indulged also in unusual "poetic forms," and later, one called "Seed Time and Harvest." [14] As he had asserted in his criticism of the critic, he was not easily crushed by ridicule. As the recipient of such forthright castigation, Sargent would have had his readers believe that he was convinced of his error and was contrite, so he printed "Our Apology" in the Pioneer, February 3, which closed: "Then it follows that what we pronounced 'wishy washy,' 'doggerel' is in fact, poetry descended from the gods. Poet grant us pardon." On February 17, while editor Sargent was absent, the Pioneer printed another "poem," inspired by, if not a "parody" of "The Washerwoman's Song." The author was not indicated but the title asserted: "I Do Not Like to Hear Him Pray." [15]

Who came off victor in this literary exchange is probably immaterial, but this "contest between giants" made an impression, at least temporarily, upon the community.

Lest the reader conclude that all this has been taken too seriously, the following, in lighter vein, by some unknown "Goosequill" appeared in the Topeka Daily Commonwealth, April 2 (not All Fools day), 1876: THE BABY'S SONG

An Eastern reader did take "The Washerwoman's Song" too seriously, however, and sent a ten dollar bill to Mr. Manlove, editor of the Monitor, accompanied by a note: Tell me, Mr. Manlove, do you know "Ironquill?" If so, was that tender, touching little song the simple image of the mind, or does the subject of his song actually live and toil in the by-ways of your city. If so hand "Ironquill" the enclosed ten dollars that when he wanders that lonely way he may leave it at the "humble cot" with my hope that an hundred hearts may beat in unison, with his, and cheer with solid sympathy the widow's bleeding heart. A lay so limpid and so soft could only flow from a pure and benevolent fountain. This letter elicited from Ware the only contemporary hint found thus far about the origin of "The Washerwoman's Song." To be sure it was negative, but that in itself eliminated a whole class of conjectural origins. Under the date February 29, 1876, Ware wrote: I regret that I cannot apply your friend's $10 bill to any one as indicated in the letter. The washerwoman is a myth and the character and scene wholly ideal. [16] There is a positive side to this negative assertion, and it issues a challenge to the historian to discover, if possible, the circumstances out of which such an "ideal" might have emerged. In the 1890's David Leahy ran a story in the Wichita Eagle [17] about "How Ware wrote it." Without specific dating, Leahy's story was that in reply to a direct question Ware related the details. In Leahy's words: "One dull day Mr. Ware was in his office and his thoughts were turned to religion by hearing a church bell ring. The following two lines flashed across his brain":

Using this as a focus, supposedly the poem was written backwards. In December, Leahy says, when Ware and the postmaster, a man of literary interests, sat on the steps of the Catholic church. Ware read the poem. His friend was silent. Ware was discouraged and stuck the poem into a pigeonhole in his desk where it rested until some time later a Monitor reporter wanted something for his column and Ware dug it out. Leahy's account included the story of the ten dollars, but with the wrong name attached and some improbable glosses. With modifications and without the more exaggerated details, a similar story was told in the Tribune-Monitor obituary notice about Ware, July 3, 1911. A kernel of truth may be involved in these tales, which serve as human-interest stories, but they do not explain anything.

On January 8, 1876, the day before the unheralded publication of "The Washerwoman's Song," the local editor of the Daily Monitor, under the title "The Last Resort" explained apologetically to his readers: Local news is so scarce that probably a few items like the following will have to be written up occasionally: "We are very sorry indeed to be called on at this juncture to announce that Mr. So-and-So's little pussy, in an attempt to get into the safe [cupboard] and try a piece of chicken, fell with a thud upon the floor and hurt its little back. … Suffice it to say no such drastic measures were necessary. Besides the argument over poetry stirred up by Nichol's efforts at versification, the fundamental issues involved in "The Washerwoman's Song" were discussed in lectures and sermons, and were the subject of public debates immediately after the publication of the poem. Two traveling lecturers appeared in Fort Scott, advertised to discuss Spiritualism. One called himself Prof. S. S. Baldwin, "Exposer of Spiritualism," and the other, W. F. Jamieson, Spiritualist. The latter attacked Christianity in the name of science and challenged any clergyman to engage in public debate. No minister accommodated Jamieson in his publicity stunt. Apparently, however, there was some demand that Christianity be defended, and that a dull winter be enlivened. Although some difference of opinion developed about how it happened, Thomas M. Nichol found himself nominated to make the sacrifice. Nichol had delivered one of the "home talent" lectures in the series arranged the preceding winter. His subject had been theological, but as a Universalist, he insisted that in the current instance he was not qualified to speak in the name of orthodox Christianity. Altogether, the debate ran through three nights, with partisans of each side claiming victory. It turned out to be good "entertainment," but there was a serious side, and unless the press reports were quite misleading, that aspect was uppermost. [18] Ware was silent throughout the period in which his poem was the favorite topic of discussion. His mind was neither unobservant nor fallow, however, and April 2, 1876, the editor of the Daily Monitor, this time, with an air of pride, made an announcement: "A beautiful little poem from the pen of the "Philosopher of Paint Creek" is printed in the MONITOR this morning." Again the poem was signed "Ironquill:" THE REAL

At the elemental folk level, but in its way as disconcerting as a child's direct reaction, was a letter from one of those people who are no doubt well-meaning, but distressingly literal minded: Right here in Southern Kansas, Mr. Ware, in almost any little garden [the Amaranth does grow]. It is unfading and perennial; blooms as well amid January snows as it does in June and July, and when hung up and dried for six months, looks as fresh and beautiful as ever. The Amaranth is a veritable flower, and no creature of imagination. [20] Of course, it was. Amaranth was a common name applicable to an order and to a genus of plants. Within the genus were many species and in some cases distinctive varieties within a species. The common garden names for those treated in gardens as flowers, are the Red Amaranths, including cockscomb or Crested Amaranth, prince's feather (princess feather) or Jacob's coat, and love-lies-bleeding. Within the genus also were such plants as Pigweed (Green Amaranth) and Tumbleweed (White Amaranth). [21] The dictionaries all agree, however, that the primary literary meaning, chiefly in poetry, was an imaginary flower that was supposed never to fade. The historical dictionaries cite usage in English literature from the early 17th century onward. Thus in Milton's Paradise Lost (iii, 353):

The title and substance of "The Real" should have made Ware's meaning clear even to the most obtuse. He sought to compare in the sharpest contrast possible, and by varied examples, "The Ideal" and "The Real." And he did it most effectively, emphasized by the off-beat final line in each stanza -- in the original printing, set off for added stress by a black line. Although not so recognized at the time, and no one since has made a serious study of Ware, the publication of "The Real" at this time may be viewed in the perspective here presented, as Ware's rejoinder to the religious debates of the preceding weeks. He was unrepentant. He was agnostic toward both Christianity and Spiritualism -- all intangibles that must be accepted on faith. The position of the agnostic must be differentiated, however, from that of the infidel -- the agnostic doubted, but he did not deny. It is one thing to render the Scotch verdict "not proven" but quite another to declare categorically that a thing is false, or does not even exist. Ware's position -- at any rate his ostensible attitude -- was that of practical pragmatist -- only tangible facts were real and provided a sense of certainty and security. Ware's was a Pragmatism, as was the case of so many other so-called practical-minded Americans of his generation, without a philosophical rationalization. That, however, was already, but unknown to Ware, being supplied by Charles S. Pierce, followed by William James, John Dewey, and others. [22] The conclusions embodied in "The Real" had not always represented Ware's position. No longer ago than 1872 he had taken the opposite side of identically the same issues and in language and ideology that were in many respects an earlier version of the same poem. At that time he had called it "The Song," arranged in rhymed prose form, and published in the Daily Monitor, October 13, 1872. It was signed Ironquill, and was among the first poetic pieces to appear over that pen name. In the Rhymes of Ironquill, it was reprinted, arranged in verse form, but scarcely changed in wording, and named "The Bird Song": THE SONG

Because the Ware poems have never before been dated, and no one has formerly undertaken to make Ware's philosophy and its background a subject of serious historical study, the relationship of these poems and their significance in terms of relations have been ignored. Although Kansans and some others have visited upon Ware an inordinate amount of highly sentimental admiration and eulogy, their adulation was too superficial for them to feel obliged to search for the structure of his thought or even to assume that it had a structure. For reasons that are not known, Ware himself, purposely or accidentally, contributed to this chaotic situation by the rule of complete irrelevance that seemed to govern the arrangement of the book versions of the Rhymes. The unpredictable manner in which contrasting types of poems rubbed elbows with each other gave an impression that the sublime and the ridiculous were never far apart, possibly only the reverse sides of the same thing. Even if, perchance, that or some other deliberately selected principle actually did govern at that time, a study of Ware according to the historical principle is long overdue. In 1872, when "The Song" was first published, Ware was in the midst of the closing hysteria of the presidential campaign. As a Greeley Liberal, and editor of the Daily Monitor, he was grinding out daily the lowest form of partisan political drivel, such as was considered necessary to win a political campaign. Whether or not "The Song" was written at this time, these were the circumstances under which it was published. Even in that context, Eugene Ware's two selves were involved; the self that was writing daily partisan political trash, which no one would be stupid enough to assume that he believed, and this other self, the poetic, the philosophical, the idealist self, who made his own decision to publish "The Song" at this particular time, even though it might have been written earlier. Indeed, the sublime and the ridiculous were in this case merely the reverse sides of Ware's two selves. But in 1872 as contrasted with 1876, what was Ware saying? What were his philosophical and theological commitments? "Hope smiles derision at assaulting facts." Apparently, then Ware was still an orthodox Congregationalist, or near to it, and substantially in accord with his father's conservatism. In "The Real," the terms Ideal and Real had been substituted for Hopes and Facts, but with the Ideal no longer paramount to the Real, Ware had reversed his basic commitments. And what about Ware's political commitments? In 1872 he was editing a liberal newspaper, though seemingly a conservative in philosophy and theology. In 1875, he published "Text," which appeared in the book version of the Rhymes under the title "The Granger's Text." This poem was a practical application of his mother's philosophy: "Smooth it over and let it go": the future, not the past, is important: THE TEXT [23]

In the record of 1875-1876, Ware was considered a political conservative, also a reversal from the position of 1872, but associated with philosophical and theological liberalism. In one or another, all the ferments of the years 1869-1876 had involved the peace of mind of many people in the Fort Scott neighborhood. A number of them have been identified by name in association with the particular ideas to which they were committed. Each fitted into his unique niche in the culture complex of Fort Scott, of Kansas, and of the United States of the 1870's. [24] But this Fort Scott of 1869-1876, with all its ambitions and inconsistencies, its dreams and disillusionments, was the background of Eugene Ware, and his poem "The Washerwoman's Song," and for that matter, of all his poetry. In the "scientific" language of the day, contemporaries might have said: the product of "the development theory." In a way, the conflict in the community was a mirror of the confusion and uncertainty troubling the minds of many of its citizens confronted with the new science of the middle years of the 19th century.

A period of quiet followed the flurry of 1876 over "The Washerwoman's Song." Although not forgotten, and reprinted again and again, a revival of interest of some magnitude occurred in 1883 in association with "An Open Letter to Hon. Eugene F. Ware," written by N. C. McFarland, commissioner of the General Land Office at Washington, D. C., a lawyer of repute from Kansas. The "Open Letter" was published first in the Topeka Daily Capital, November 18, and Ware's reply, November 25, 1883, a poem without a title other than the salutation: "To Hon. N. C. McFarland, Washington, D. C." and introduced by a short note to the editor. A name was not assigned to the poem, apparently, until it appeared in the first edition of Rhymes of Ironquill, in 1885, as "Kriterion." [25] Thus far the exact set of circumstances have not been determined which stimulated McFarland to write his letter, nor which explain the remarkable response to the letter and to Ware's reply, along with the original "Washerwoman's Song." The casual but appreciative comment upon the "Song" over the intervening years, 1877 to 1882, was one thing, but the enthusiasm of 1883 was quite another. When, on November 18, the Sunday Capital printed the "Open Letter," it was done without fanfare: "The Washerwoman's Song" was printed at the top of the column, the letter occupying about one and one half columns. [26] McFarland's letter is rather long to print here in its entirety, but these are the most pertinent parts: DEAR SIR: -- I have read again and again with indescribable pleasure and sadness, your "Washerwoman's Song," -- pleasure because it is really beautiful, and voices correctly the joy of Christ's poor ones; sadness because you say you are shut out from a hope, which, though not always so bright and cheerful, is worth more than all else this world affords. You will pardon me for addressing you in this public manner, for I know that many men of intellect and culture occupy positions not dissimilar to your own, and I hope in this way to make some suggestions which will reach both you and them, and not be inappropriate to the subject, whether they shall prove valuable or useless. Reading between the lines, I think I can see a thoughtful interest, a sort of inquiry, a desire to possess a hope like, or at least equal, to the heroine of your song. If this were not so, I could scarcely interest myself sufficiently to write you, for I confess I have but little patience with that class of criticisms that flippantly brushes aside the motives of God, Christ and immortality, as fit only for the contemplation of "women and children." To me these mysteries are the profoundest depths. I have no plummet heavy enough, nor line long enough to reach the bottom. I may push them aside for a time, while other things engross me, but they come unbidden again and again across my path. Is it so with you. . . . The Daily Monitor, November 20, in Ware's home town wrote proudly: The open letter addressed to Hon. E. F. Ware by Mr. N. C. McFarland, published this morning, adds new interest to the "Washerwoman's Song," which is considered by many to be Ware's best composition. There can be no higher evidence of the merit of a poem than the fact that it arouses and calls into active being such eloquent and burning thoughts as those contained in Mr. McFarland's letter . . . . D. W. Wilder's editorial on McFarland's letter stated that the purpose was to give the poet faith in God and to remove his doubts; that the spirit embodied in the letter was as pure as that expressed in the poem. It does not have an "I-am-better-than-thou" tone, and in reference to the purpose it says that perhaps the poet could tell if the letter fulfilled its mission. "Noble letters between two true men would set an example to theological disputants -- who always fight and who are not Christ-like." [27] Another communication on the poem and McFarland's letter was by D. P. Peffley, of Fort Scott, dated November 25, and printed in the Daily Monitor, November 28, the day before Thanksgiving. It contained much of the same thoughtfulness and expression, and was nearer to earth: I have found much to interest me in reading the letter of Mr. McFarland, reprinted in your last issue, discussing Mr. Ware's poem. After the mad whirl of personal politics, which periodically seems to swallow up everything of such a nature, it is indeed gratifying to those whose sentiments and affections cling to the little circle lighted by the domestic lamp to be allowed a comer in the indispensable and all visiting newspaper. The poem I have read before. I have also seen beauty in it; not the Miltonic beauty of grand imaginative flights, soaring into the loftiest empyrean, where ordinary minds dare not follow; not the giantlike grasp of intellect that seizes something abstract, unreal, and tortures it till it gives out its essence in labored metrical lengths, its beauty lost to untrained intellects in its incomprehensibleness, but the simple beauty of naturalness, of truthfulness. One hears the very "rub" of the washboard in its meter. It requires not the genius of a Gustave Doré to picture to oneself the home it describes, the hopeful sad face of the woman bending over the tub, set perhaps on an upturned chair, the splashed child, the miscellaneous heap of "duds." Alas! the scene too often naturalizes for us. Among other things, these two letters show how greatly times have changed. People took more time then, in writing such comments and in contemplating poetry in this profound sense. What now seems somewhat wordy and beside the point served as recreation as well as literary art, and when a series of events such as this developed, it was like the serial on the inside of the back page, except that anyone could offer something to the growth of the train of letters. Also, discussions close to the hearts of the people were carried on through the newspapers, often in a literary and informative fashion, taking the place of modern "canned" amusement. An editorial in the Sunday Capital, November 25, 1883, was headed, "The New Poem of Hon. Eugene Ware": It will be unnecessary for us to call the attention of our readers to the beautiful poem from Hon. Eugene Ware, of Fort Scott, addressed to Hon. N. C. McFarland in reply to his letter which appeared in the Capital last Sunday. The letter of Judge McFarland has been widely copied in the weekly press of Kansas. The poem is rich in pure, deep and reverential feeling, delicate and most beautiful in expression [,] a most appropriate reply to Judge McFarland's thoughtful letter. In another column of the same page. Ware's contribution was printed with the heading "Hon. Eugene Ware to Hon. N. C. McFarland": TO THE EDITOR OF THE CAPITAL: In reprinting the "Reply," the Junction City Union, December 1, 1883, commented: "The letter and the two poems constitute a cheerful oasis in the slush the newspaper man is called upon to deal with." The lack of a name for the poem, besides the term "Reply" was a handicap, but a temporary title was supplied; one of more logical significance by the Emporia News in its Holiday edition [December 25], 1883: "It May Be Reality." The Manhattan Nationalist, November 23, 1883, put Ware "at the head of Kansas poets," and suggested, "if he would cultivate his talents in this direction, might secure a national fame." [29] One of the most remarkable aspects of both the Ware episodes, 1876 and 1883, is the absence of personal hostility toward Ware, or ridicule of his verse or of his ideas. With due regard to the allowances that properly belong to any attempt at generalization, the dictum of "FSM," in 1876, about Western people and religion may again apply -- respect for sincere faith even when agnostic toward it. [30] In Ware's reply to McFarland, which will be referred to henceforth by the later name "Kriterion," what was his position on religious orthodoxy? In "The Washerwoman's Song" Ware had assumed the position of doubt, softened by tolerant compassion. In "The Real" he had stood his ground, but in "Kriterion" he appeared to hedge Perhaps -- this immortality May be indeed reality. In order to appreciate more accurately and adequately what had happened to Ware's thinking and feeling, it is well to go still farther back into the record. On October 23, 1870, the Daily Monitor had printed a poem over the initials "EFW," the first of his poems found there with so explicit an identification. This represented orthodox theological certainty. "The Washerwoman's Song" revealed Ware at the other extreme, a confessed agnostic, but also certain he had found truth. The text of "The Palace," of 1870, which Ware never saw fit to revive or revise for book publication in the Rhymes of Ironquill, follows: THE PALACE

The contrast between the texts of "The Palace" and of the "Kriterion" is made the more sharp by the titles supplied for the latter by the Emporia News, "It May Be Reality." Ware had reversed himself once, and had gone part way apparently in a return, but had not completed the cycle. Yet, candor must insist upon sticking to the record, although a good case could be made for the view that privately Ware had not abandoned the position of 1876 on "The Washerwoman's Song," and "The Real," but purely as a matter of expediency, had made a concession to what "FSM" had insisted Western People demanded in "fair play" on matters of difference in religion -- a sincere respect for a genuine religious character, though not necessarily acceptance of religious form. Unknown is the reason why Ware selected, apparently belatedly, the title "Kriterion," both the idea and the Greek spelling. Yet the public accepted the name without any question about the meaning or about orthography.

All this was written prior to a full realization by the present author of the fact that there was a private view of the "Kriterion" episode quite different from the public view -- in fact, a contradiction of both the main facts and the interpretation just given them. In order to reconstruct history as a whole, the private view must now be stated. The "Kriterion" was not a new poem, and it was not written in reply to Judge McFarland. Already it had been published under its proper title, "Kriterion," and over his pen name Ironquill, in the Daily Monitor, August 16, 1874, or nearly nine years prior to McFarland's "Open letter." That was long enough before the episode of 1883 that those who may have once known of the earlier printing had long since forgotten. Besides, in 1874, so far as can be discovered, the poem did not attract any attention either at home or abroad. Why should it have created so remarkable a flurry in 1883? Why did Ware misrepresent it; offer it without its title, and as a reply to the open letter? Surely after the remarkable experience with "The Washerwoman's Song" he was aware that he was in the presence of an occasion that might involve portentous responses. Even though unprepared to answer with a new production, and like the preacher who turned his sermon barrel upside down to select off the bottom, he must have weighed the choice with care. Why did he perpetuate the hoax in the book publication of the Rhymes of Ironquill, in 1885, and in the many editions thereafter, by printing the McFarland Open Letter as the link between "The Washerwoman's Song" and "Kriterion?" But more important than this physical manipulation of tangible facts, is the violence which Ware committed upon himself; upon his private intellectual and religious integrity. As pointed out already, if "Kriterion" had been written in response to McFarland, it meant a retreat in thought. In its true chronology, however, it was a waystation along a straight-line transition from the orthodoxy of "The Palace," through "Kriterion," to the agnosticism of "The Washerwoman's Song." Already, the suggestion has been made that possibly it was a concession to his public, an act of expediency, without necessarily being a private reversal. That view now becomes more insistent, but for a quite different reason. Henceforth the student of Ware's poetry, and admirers of "The Washerwoman's Song," or of "Kriterion" as individual poems must keep in mind these two views, the private and the public, and their irreconcilability. Viewed as a whole, truth is complex and challenging.

DR. JAMES C. MALIN, associate editor of The Kansas Historical Quarterly and author of several books relating to Kansas and the West, is professor of history at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. 1. The wording used here is essentially that of the original printing in the Fort Scott Daily Monitor, January 9, 1876, but the punctuation follows that of the third edition of the Rhymes of Ironquill, 1892. 2. The date given by D. W. Wilder, Annals of Kansas (1886), p. 698, is an error. He printed it in the original wording. 3. At this particular time most of the first column of the editorial page was identical in both papers, and was printed from the same type. Later in the year the Commercial was discontinued. 4. Daily Times, January 16; Daily Commercial, January 17, 1876. 5. Is it unkind to call attention to the newspaper's error in the title of the poem? 6. Parsons Sun, January 22; Oswego Independent, February 5, 1876, both "patent outsides." 7. Later Ware found it necessary to cancel this engagement. Parsons Sun, March 4, 1876; Daily Monitor, February 19, March 7, 1876. 8. In the sixth line of stanzas one and four, the words "rubs and rubs" were a reflection of Ware's original version of "The Washerwoman's Song," which used them in the sixth stanza, line one, instead of "rubs and scrubs," used in the book printings. 9. Daily Monitor, December 23, 1875. 10. Kansas state census, 1875 (Ms.), v. 5, Bourbon county. City of Fort Scott, p. 55; his name appeared a second time, p. 91, with an age of 30, in 1875; State Board of Agriculture, The Third Annual Report . . ., 1874, p. 75; Daily Monitor, August 28, December 3, 9, 1874, February 26, March 6, 1875. He was later to have a remarkable career elsewhere. 11. Monitor, January 30 (Sunday), 1876. 12. The authorship of the headline is not clear; if the origin was Nichol, at least, the editor accommodated by not "killing" it. 13. Daily Monitor, February 1, 1876. 14. Ibid., February 3, 15, 1876. 15. The Mirror and Newsletter, Olathe, February 24, 1876; the Arkansas City Traveler, March 29, 1876, were among those printing this "poem." 16. Fort Scott Daily Monitor, March 1, 1876. 17. Reprinted in the Topeka State Journal, January 10, 1898. 18. The episode can be followed, in the local papers, the Daily Monitor, and the Pioneer, for the two weeks' period beginning January 31. 1876. 19. The reading of the poem printed here, except for the correction of a typographical error, is the original version as given in the Daily Monitor, April 2, 1876. In the selected poems published later in book form under the title (with variations) Rhymes of Ironquill (1885 and later) substantial changes in wording were introduced. 20. Parsons Eclipse, April 13, 1876, reprinted in the Fort Scott Pioneer, April 27, 1876. 21. Asa Gray, Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States. … Sixth Edition by Sereno Watson and John M. Coulter (New York, 1889); Harlan P. Kelsey and William A. Dayton, editors. Standardized Plant Names, Second Edition (Harrisburg, Pa., (1942); The Oxford English Dictionary, Being a Reissue … of a New English Dictionary on Historical Principles … (Oxford, 1933); The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the English Language (New York, First Edition, 1891, Revised, (1913); Webster's New International Dictionary of the English Language, Second Edition, Unabridged (Springfield, 1950). The common spelling is Amaranth, but the correct form is Amarant. 22. James C. Malin, "Notes on the Writing of General Histories of Kansas: Part One, The Setting of the Stage," Kansas Historical Quarterly, v, 21 (Autumn, 1954), pp. 192-202; On the Nature of History (Lawrence, The Author, 1954), ch. 3, especially p. 77; The Contriving Brain and the Skillful Hand (Lawrence, The author, 1955), pp. 348-353. 23. Daily Monitor, May 16, 187S, by "The Philosopher of Paint Creek." The version given here is that printed in the Monitor. At this time Ware was using two pen names; each for a different kind of rhymes. To be discussed elsewhere. 24. See the present author's articles dealing with Fort Scott philosophers, Kansas Historical Quarterly, v. 24 (1958), pp. 168-197, 314-350. 25. If an earlier use was made of that name between 1883 and 1885, the present writer has not found it. 26. The first line of the sixth stanza read "rub and scrub," instead of the original "rub and rub." 27. Hiawatha World, November 22, 1883. 28. The wording and arrangement of the lines is that of the poem as published in the Capital. The punctuation, however, follows that of the third edition of the Rhymes of Ironquill (1892). In that edition, for the first time, changes were introduced including the lines seven, eight, and nine of the third stanza which were revised to read:

29. In its issue of November 29, 1883, the Lyndon Journal, contrasted McFarland and Sen. John J. Ingalls to the disadvantage of the latter as a sceptic. In his Troy Kansas Chief, December 13, 1883, Sol Miller blundered in his reading of the Journal's comment, and attributed to it a comparison of Ware and Ingalls; Ware the Christian and Ingalls the sceptic. Miller preferred Ingall's brains to Ware's piety. This is one of the few unkind Kansas reactions to Ware's poetry, and both its error and its animus were evident. If Ware was a candidate for the United States senate, Miller suggested, then, "perhaps there is a necessity for starting a religious boom in his favor." 30. Topeka Commonwealth, April 9, 1876. |